Ivan Pavlov: The Architect of Classical Conditioning and Beyond

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (1849–1936) was a Russian physiologist whose pioneering research on digestion unexpectedly revolutionized psychology through the discovery of classical conditioning. Best known for his experiments with dogs, Pavlov demonstrated how learning could occur through association, laying a foundational stone for behaviorism and influencing fields from education to neuroscience. This article explores Pavlov’s life, his seminal work on conditioning, his physiological contributions, and his enduring legacy as of March 2, 2025.

Early Life and Scientific Beginnings

Born on September 26, 1849, in Ryazan, Russia, Pavlov was the son of a village priest and initially trained for the clergy. However, inspired by the scientific writings of Charles Darwin and Russian physiologist Ivan Sechenov, he abandoned theology for science. In 1870, he enrolled at the University of St. Petersburg, excelling in physiology and earning a medical degree in 1879 from the Imperial Military Medical Academy. Pavlov’s early career focused on digestion and the nervous system, earning him a reputation as a meticulous experimentalist. In 1890, he became a professor at the Military Medical Academy and director of its physiology department, a role that provided the resources for his transformative research.

Pavlov’s dedication to empirical rigor was legendary. He worked long hours, often in austere conditions, and demanded precision from himself and his team. His efforts earned him the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1904 for his work on digestive glands—well before his fame in psychology emerged.

The Discovery of Classical Conditioning

|  |

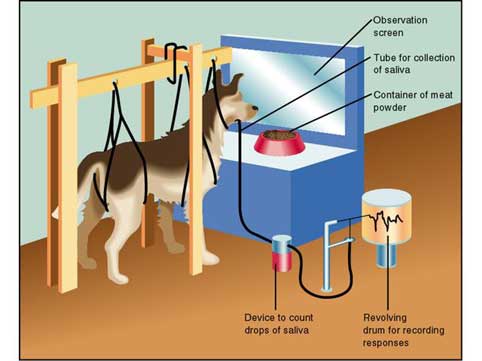

Pavlov’s most famous contribution arose serendipitously while studying digestion in dogs. He surgically fitted dogs with fistulas to measure salivary responses to food, expecting a straightforward physiological study. However, he noticed something curious: the dogs began salivating before food was presented, triggered by cues like the sight of the lab assistant or the sound of footsteps. This “psychic secretion,” as Pavlov initially called it, suggested that salivation wasn’t just a reflex but a learned response tied to environmental stimuli.

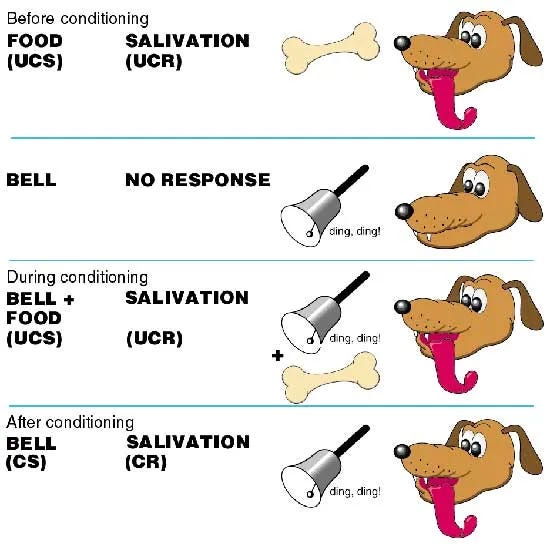

To investigate, Pavlov designed controlled experiments. In his classic setup, a dog was exposed to a neutral stimulus—such as a bell ringing—followed by an unconditioned stimulus (UCS), like food, which naturally elicited salivation (the unconditioned response, or UCR). After repeated pairings, the bell alone (now a conditioned stimulus, or CS) triggered salivation (the conditioned response, or CR). This process, which Pavlov termed “conditioned reflex,” demonstrated that organisms could learn to associate neutral events with biologically significant ones.

Key concepts from his work include:

- Acquisition: The initial learning phase where the CS and UCS are paired.

- Extinction: When the CS is presented repeatedly without the UCS, the CR weakens (e.g., the bell stops eliciting salivation).

- Spontaneous Recovery: After extinction, the CR can briefly reappear if the CS is presented again after a rest period.

- Generalization: The CR extends to stimuli similar to the CS (e.g., a similar tone also triggers salivation).

- Discrimination: The ability to distinguish the CS from dissimilar stimuli, refining the response.

Pavlov’s Tower of Silence—a soundproof lab built in 1924—minimized external variables, ensuring his findings reflected true associative learning. His experiments shifted from digestion to psychology, revealing a mechanism underlying habit formation and behavior.

Physiological Foundations: Digestion and Reflexes

Before conditioning, Pavlov’s Nobel-winning research focused on the physiology of digestion. He explored how the nervous system regulates glandular secretions, particularly in the stomach and salivary glands. Using dogs with surgically implanted tubes, he measured how factors like food type, chewing, and even psychological states influenced digestion. Pavlov demonstrated that the vagus nerve played a key role in coordinating digestive responses, advancing knowledge of autonomic functions.

His conditioning work built on this foundation, viewing conditioned reflexes as extensions of innate reflexes. Pavlov saw the brain as a “switchboard” connecting stimuli to responses, with conditioning reflecting the nervous system’s adaptability. This physiological lens distinguished his approach from later behaviorists who avoided internal mechanisms.

Personality Types and Temperament

Later in his career, Pavlov extended his research to temperament, hypothesizing that individual differences in conditioning reflected nervous system properties. Drawing on Hippocratic humoral theory, he proposed four personality types based on excitation and inhibition:

- Strong Excitatory (Choleric): Quick to condition, impulsive, aggressive.

- Strong Inhibitory (Phlegmatic): Slow, calm, resistant to overstimulation.

- Balanced (Sanguine): Adaptable, sociable, moderate in responses.

- Weak (Melancholic): Sensitive, easily overwhelmed, slow to learn.

He linked these to the cerebral cortex’s strength and balance, testing them experimentally by varying conditioning intensity. While speculative, this work influenced later studies in behavioral genetics and personality psychology.

Impact on Psychology and Beyond

Pavlov’s discovery of classical conditioning had profound effects:

- Behaviorism: John B. Watson adopted Pavlov’s principles to develop behaviorism, emphasizing observable behavior over mental states. Watson’s “Little Albert” experiment (1920), conditioning fear in a child, directly applied Pavlovian methods.

- Education: Teachers use associative learning to reinforce habits, like pairing praise (UCS) with effort (CS) to boost motivation (CR).

- Therapy: Classical conditioning underpins treatments like systematic desensitization for phobias, where feared stimuli are re-associated with calm responses.

- Neuroscience: Pavlov’s focus on reflexes inspired research into synaptic plasticity and neural learning mechanisms.

As of March 2, 2025, his ideas resonate in fields like advertising (pairing products with positive emotions) and AI, where algorithms mimic associative learning.

Experimental Rigor and Methodology

Pavlov’s methodology set a gold standard. He controlled variables meticulously, using metronomes, lights, and tones as stimuli, and measured responses with precision (e.g., drops of saliva). His insistence on replication and objectivity influenced experimental psychology’s scientific turn. However, his reliance on dogs—sometimes dozens in a single study—raised ethical questions by modern standards, though such concerns were absent in his era.

Criticisms and Limitations

Pavlov’s work faced critique:

- Reductionism: His focus on reflexes oversimplified complex human behaviors like reasoning or creativity, which behaviorists later struggled to explain.

- Species Gap: Applying dog-based findings to humans ignored cognitive and cultural factors.

- Physiological Bias: His emphasis on nervous system mechanisms clashed with behaviorism’s avoidance of internal processes, creating a theoretical tension.

Later research, like Robert Rescorla’s contingency theory (1967), refined Pavlov’s model by showing that predictability, not just pairing, drives conditioning.

Personal Context and Legacy

Pavlov’s life unfolded amid upheaval—World War I, the Russian Revolution, and Stalinism. A critic of communism, he nonetheless stayed in Russia, supported by Lenin for his scientific prestige. Despite personal tragedies (e.g., losing a son in the civil war), he worked tirelessly until his death on February 27, 1936, from pneumonia.

His legacy is vast. Beyond the iconic “Pavlov’s dogs,” he authored Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex (1927), a seminal text. The Pavlovian Society and countless citations keep his ideas alive. In 2025, his work informs behavioral therapies, educational strategies, and neural network models, proving its timeless relevance.

Conclusion

Ivan Pavlov’s journey from digestive physiologist to psychological pioneer exemplifies scientific serendipity. His discovery of classical conditioning revealed how associations shape behavior, bridging physiology and psychology with enduring clarity. While his reductionist lens drew scrutiny, his empirical rigor and insights into learning remain foundational. As of March 2, 2025, Pavlov’s legacy echoes in labs, classrooms, and beyond, a testament to the power of a bell, a dog, and a curious mind.