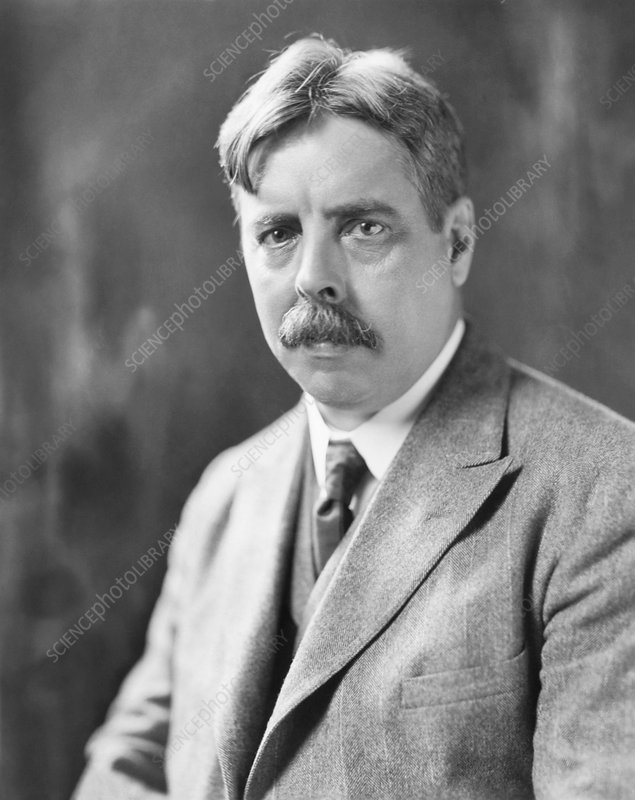

Edward Thorndike: Pioneering Learning Theory and the Foundations of Educational Psychology

Edward Lee Thorndike (1874–1949) was an American psychologist whose groundbreaking work on learning and behavior laid the scientific groundwork for modern educational psychology and influenced the rise of behaviorism. Best known for his theory of connectionism and the Law of Effect, Thorndike’s research bridged animal behavior and human learning, offering insights that remain relevant as of March 2, 2025. This article explores Thorndike’s life, his key theories, experimental methods, and the enduring legacy of his contributions.

Early Life and Academic Journey

Born on August 31, 1874, in Williamsburg, Massachusetts, Thorndike exhibited intellectual curiosity from a young age. He graduated from Wesleyan University in 1895, where he was exposed to philosophy and psychology, before pursuing graduate studies at Harvard University under William James. At Harvard, Thorndike began experimenting with animal behavior, a passion that deepened when he transferred to Columbia University. There, under the mentorship of James McKeen Cattell, he earned his Ph.D. in 1898 with a dissertation titled Animal Intelligence: An Experimental Study of the Associative Processes in Animals. This work, the first psychological study to use non-human subjects extensively, marked the beginning of his influential career.

Thorndike spent most of his professional life at Teachers College, Columbia University, where he conducted research, taught, and published prolifically until his death on August 9, 1949. His career coincided with a shift in psychology toward empirical rigor, and his work helped shape this transition.

The Theory of Connectionism

Thorndike’s most significant contribution to psychology is his theory of connectionism, which posits that learning results from associations—or "connections"—formed between stimuli (S) and responses (R). Unlike earlier theories that speculated about internal mental states, Thorndike argued that learning could be explained through observable behavior, making his approach a precursor to behaviorism. He believed these S-R bonds are strengthened or weakened based on their consequences, a concept he explored through meticulous experiments.

Connectionism emerged from Thorndike’s view that intelligence reflects an organism’s ability to form such connections. He saw humans as advanced learners due to their capacity for more complex associations, yet he maintained that the fundamental mechanisms of learning were consistent across species.

The Puzzle Box Experiments

Thorndike’s theory was grounded in his famous puzzle box experiments, primarily conducted with cats. He designed wooden boxes—roughly 20 inches long, 15 inches wide, and 12 inches tall—with a door that opened when an animal inside triggered a lever, button, or string. A hungry cat was placed in the box, and food was positioned outside as an incentive. Initially, the cat would scratch, claw, or move randomly (trial-and-error behavior) until it accidentally activated the release mechanism. Over repeated trials, Thorndike recorded the time it took for the cat to escape, observing a pattern: escape times decreased as the cat learned to associate the specific action (e.g., pressing the lever) with the reward (freedom and food).

These experiments produced a learning curve, often S-shaped, showing gradual improvement followed by a plateau once the behavior was mastered. Thorndike interpreted this as evidence that learning occurs incrementally through trial and error, not sudden insight—a finding that challenged prevailing notions of animal cognition.

The Laws of Learning

From his research, Thorndike formulated three primary laws of learning, which became foundational to his theory:

- Law of Effect

Thorndike’s most famous principle, the Law of Effect, states that responses followed by a satisfying outcome are more likely to be repeated, while those followed by discomfort are less likely to recur. In the puzzle box, pressing the lever led to escape and food (satisfaction), strengthening that S-R connection, while ineffective actions weakened over time. Initially proposed in 1898, Thorndike later refined this law in 1932, emphasizing that rewards strengthen associations more reliably than punishments weaken them. This idea profoundly influenced B.F. Skinner’s operant conditioning. - Law of Exercise

This law has two parts: the Law of Use, which asserts that frequent repetition strengthens S-R connections, and the Law of Disuse, which suggests that unused connections weaken over time. For example, a skill practiced regularly (like playing an instrument) becomes ingrained, while neglect leads to forgetting. By 1932, Thorndike acknowledged that this law was less universal than the Law of Effect, as repetition alone didn’t guarantee learning without motivation or reward. - Law of Readiness

This law highlights the role of an organism’s preparedness to act. When ready to respond, acting is satisfying, and being prevented is annoying; when unprepared, being forced to act is frustrating. In educational terms, a motivated student learns more effectively than one coerced into a task.

Thorndike also proposed subordinate laws, including Multiple Response (trying various actions until success), Set or Attitude (predispositions affect learning), Prepotency of Elements (focusing on relevant stimuli), and Response by Analogy (applying past experiences to new situations). These refined his theory, addressing nuances in learning behavior.

Contributions Beyond Learning Theory

Thorndike’s work extended beyond connectionism. With Robert S. Woodworth, he studied the transfer of learning, publishing a 1901 paper showing that skills learned in one context don’t automatically enhance learning in unrelated areas unless common elements are present. This finding supported practical, relevant curricula over broad, generalized training.

He also explored human intelligence, identifying three types: abstract (conceptual understanding), mechanical (spatial or object manipulation), and social (interpersonal skills). Thorndike argued that intelligence wasn’t a single trait but a capacity for forming connections, measurable through performance rather than introspection.

In applied psychology, Thorndike tackled industrial problems, developing employee testing methods, and contributed to educational measurement with works like An Introduction to the Theory of Mental and Social Measurements (1904). His books on arithmetic, reading, and adult learning further solidified his role as a founder of educational psychology.

Impact on Psychology and Education

Thorndike’s work had a seismic impact:

- Behaviorism: His emphasis on observable S-R associations and reinforcement paved the way for behaviorism. Skinner built on the Law of Effect to develop operant conditioning, while Thorndike’s rejection of unobservable mental states aligned with John B. Watson’s principles.

- Education: Thorndike’s laws informed teaching strategies—motivating students (readiness), using practice (exercise), and rewarding success (effect). His research supported structured, goal-directed learning over abstract theorizing, influencing modern pedagogical design.

- Comparative Psychology: His animal studies shaped the field for decades, establishing rigorous experimental standards.

As of March 2, 2025, Thorndike’s ideas resonate in digital learning environments, where reinforcement (e.g., badges) and repetition (e.g., drills) enhance engagement, and in behavior analysis, such as applied behavior analysis (ABA) for developmental disorders.

Criticisms and Limitations

Thorndike’s work isn’t without critique:

- Mechanistic View: Critics argue that connectionism oversimplifies human learning, reducing it to automatic S-R bonds and neglecting higher reasoning or creativity.

- Animal-Human Gap: Extrapolating from cats to humans raised questions, as human cognition involves language and abstract thought beyond trial and error.

- Narrow Focus: The theory’s emphasis on associations overlooks emotional or social factors in learning.

- Historical Context: Thorndike’s writings reflected the era’s biases—racist, sexist, and eugenic ideas—that led Teachers College to remove his name from a building in 2020, complicating his legacy.

Conclusion

Edward Thorndike’s work transformed our understanding of learning, blending empirical precision with practical application. His connectionism theory, anchored by the Law of Effect, offered a scientific lens on behavior that bridged psychology and education. While his mechanistic approach drew criticism, its influence on behaviorism, educational practice, and comparative psychology is undeniable. As of March 2, 2025, Thorndike’s legacy endures in classrooms, research labs, and digital tools, a testament to his pioneering vision of learning as a process of forging connections—trial by trial, reward by reward.