Bloom’s Taxonomy: A Framework for Learning and Cognitive Growth

Bloom’s Taxonomy, first introduced in 1956 by educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom and a team of collaborators, stands as one of the most influential models in education. Designed to classify educational objectives and promote higher-order thinking, this framework provides a structured approach for educators to design curricula, craft assessments, and foster intellectual development in students. Over time, it has evolved to meet modern demands while remaining a cornerstone of pedagogical theory. This article explores the origins of Bloom’s Taxonomy, its structure, its applications, revisions, and its enduring relevance as of March 2, 2025.

Origins and Purpose

Benjamin Bloom, born in 1913 in Lansford, Pennsylvania, was an American educational psychologist committed to improving learning outcomes. In 1956, he led a team—including Max Englehart, Edward Furst, Walter Hill, and David Krathwohl—to publish Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals, Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. This work emerged during a period when education sought to shift beyond rote memorization toward measurable, meaningful learning goals. Bloom and his collaborators aimed to create a common language for educators to articulate and assess cognitive skills systematically.

The original taxonomy focused on the cognitive domain, encompassing intellectual abilities such as thinking, understanding, and problem-solving. Later extensions addressed the affective domain (emotions and attitudes) and psychomotor domain (physical skills), but the cognitive domain remains the most widely recognized and applied.

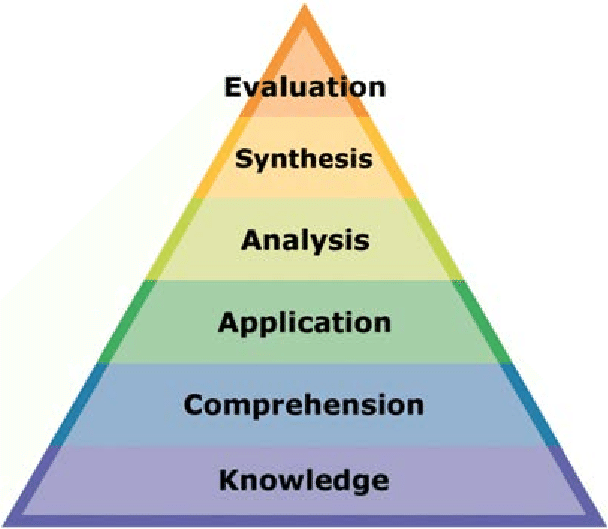

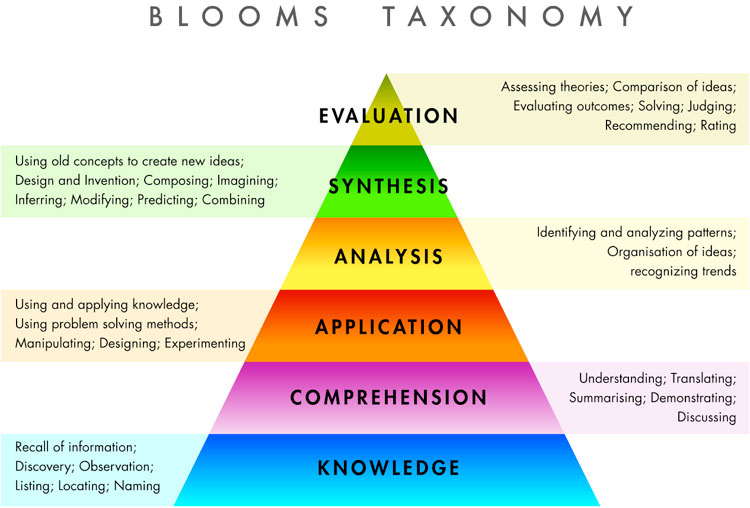

The Original Bloom’s Taxonomy: Six Levels of Cognition

Bloom’s Taxonomy is structured as a hierarchy of six cognitive levels, progressing from basic to complex thinking skills. Each level builds on the previous one, forming a ladder of intellectual development. Here’s a detailed breakdown:

- Knowledge

The foundational level involves recalling facts, terms, or basic concepts. This simplest form of learning often relies on memorization. Examples include reciting multiplication tables, listing historical events, or naming parts of a machine.- Key verbs: Define, list, recall, identify.

- Comprehension

Learners demonstrate understanding by interpreting or summarizing information in their own words, moving beyond rote recall to grasp meaning. For instance, explaining the significance of a scientific discovery or paraphrasing a story’s plot falls here.- Key verbs: Describe, explain, summarize, interpret.

- Application

This level requires using knowledge in new situations or solving problems with learned concepts, bridging theory and practice. Examples include applying a formula to calculate interest or using grammar rules to construct sentences.- Key verbs: Apply, use, demonstrate, solve.

- Analysis

Learners break down information into parts and examine relationships or structures, engaging in critical thinking. This might involve identifying causes of an event or comparing two literary works.- Key verbs: Analyze, compare, differentiate, examine.

- Synthesis

At this creative stage, students combine elements to form something new. Examples include designing an experiment, composing a poem, or proposing a solution to a societal issue.- Key verbs: Create, design, compose, formulate.

- Evaluation

The highest level involves making judgments about the value or quality of ideas, methods, or products based on criteria. This could mean critiquing a policy’s effectiveness or assessing an argument’s validity.- Key verbs: Judge, evaluate, critique, justify.

This hierarchy assumes mastery of lower levels is necessary for success at higher ones, offering a scaffold for cognitive growth.

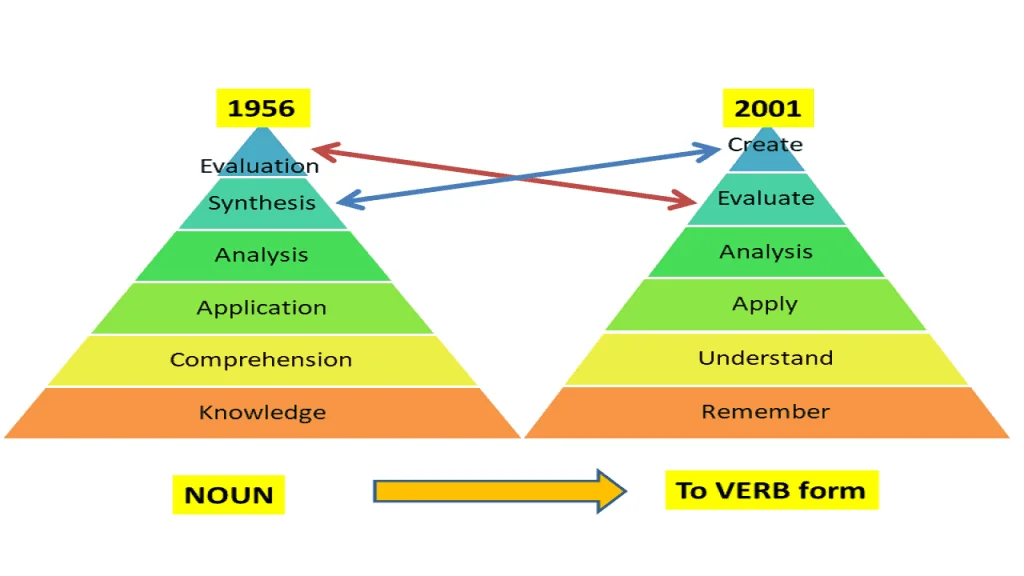

The Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy (2001): A Modern Evolution

By 2001, shifts in educational theory and cognitive science prompted a revision of the original taxonomy. Led by Lorin Anderson, a former student of Bloom, and David Krathwohl, an original contributor, the updated framework was published in A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. The revision retained the six levels but introduced key changes to enhance its relevance and usability:

- Shift to Action-Oriented Verbs

The levels were renamed from nouns to gerunds—Remembering, Understanding, Applying, Analyzing, Evaluating, and Creating—emphasizing learning as an active process. This shift aligned with student-centered pedagogies, focusing on what learners do. For example, “Knowledge” became “Remembering” (e.g., recalling key dates), and “Comprehension” became “Understanding” (e.g., explaining a concept), making objectives more actionable. - Reordering the Hierarchy: Elevating Creativity

The top two levels swapped positions, with “Creating” replacing “Evaluation” as the pinnacle. This change reflected the belief that generating new ideas or products (e.g., inventing a tool) requires greater cognitive effort than judging existing ones (e.g., critiquing a study). “Evaluating” moved to the fifth level, while “Creating” crowned the hierarchy, aligning with a growing emphasis on innovation. - Introduction of the Knowledge Dimension

A second axis—the Knowledge Dimension—categorized content into four types:- Factual Knowledge: Basic details (e.g., knowing chemical elements).

- Conceptual Knowledge: Theories or systems (e.g., understanding supply and demand).

- Procedural Knowledge: Methods or skills (e.g., solving equations).

- Metacognitive Knowledge: Self-awareness of thinking (e.g., reflecting on learning strategies).

This grid allowed educators to pair cognitive processes with content, such as “Apply procedural knowledge” (e.g., use a coding technique) or “Analyze conceptual knowledge” (e.g., compare economic models).

The revision drew on advances in metacognition and constructivist learning, offering a flexible, practical tool for modern education.

Applications in Education

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a versatile framework with broad applications:

- Curriculum Design: Educators sequence objectives from basic recall to advanced skills. A history unit might start with “Remembering” key dates and end with “Creating” an alternate timeline.

- Assessment: It shapes questions and tasks, from “What is photosynthesis?” (Remembering) to “Design a sustainable ecosystem” (Creating).

- Instructional Strategies: Activities align with levels, such as discussions for “Analyzing” or projects for “Creating.”

- Differentiation: It tailors tasks to learners’ abilities, scaffolding from simple to complex.

Beyond classrooms, Bloom’s principles influence corporate training, instructional design, and technology development, where critical thinking is key.

Strengths and Criticisms

The taxonomy’s clarity and practicality are widely praised. It elevates learning beyond memorization, encouraging critical and creative thinking, and its hierarchy provides a roadmap for skill-building. The revised version’s flexibility enhances its adaptability across contexts.

Critics, however, note limitations:

- Oversimplification: The strict hierarchy may oversimplify cognition, as real-world thinking often blends levels (e.g., analyzing while applying).

- Cultural Bias: Its focus on individual, abstract reasoning may not suit all learning cultures.

- Narrow Scope: The cognitive emphasis sidelines emotions and physical skills, prompting calls for broader frameworks.

Despite these critiques, its adaptability keeps it relevant.

Bloom’s Taxonomy in the Digital Age

As of today, Bloom’s Taxonomy thrives in technology-enhanced learning:

- Online Education: Platforms use it to structure courses, with quizzes for “Remembering” and simulations for “Creating.”

- Artificial Intelligence: AI tools personalize tasks based on Bloom’s levels, adapting to learner progress.

- Critical Thinking: In an information-rich world, it helps students analyze and evaluate data, combating misinformation.

Educators integrate it with digital tools like coding (Creating), data software (Analyzing), and virtual debates (Evaluating), ensuring its principles meet 21st-century needs.

Conclusion

Bloom’s Taxonomy is more than a classification system—it’s a blueprint for intellectual growth. From its 1956 origins to its 2001 revision, it has guided educators in cultivating thoughtful, capable learners. By breaking cognition into actionable stages, it demystifies learning and elevates goals from recall to creativity. As education evolves with technology and global challenges, Bloom’s Taxonomy remains a timeless framework, shaping how we teach, learn, and innovate in 2025 and beyond.